Even though we’re not supposed to have “favorites,” the Fusoris astrolabe is one of the MOL team’s favorite objects. Currently housed in Harvard History of Science’s Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments, it is one of very few medieval items in CHSI’s collection. It is on public display in the permanent Putnam Gallery in Harvard’s Science Center.

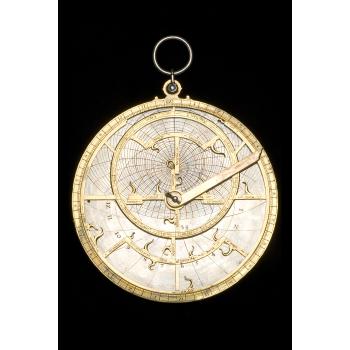

Visually, the astrolabe is attention-grabbing mainly because of how complicated it appears. The main body of a typical astrolabe would consist of a disk about six inches (15 cm) in diameter and ¼ inch (6 mm) thick, the mater, which was carved to hold interchangeable plates, or tympans, but still show calculatory information on the ring at the edge of the mater. The interchangeable plates set into the mater were calibrated to a given latitude, and were engraved with circles of altitude and azimuth for that latitude. Over the tympan was fitted another disk, called the rete (meaning “net” in Latin), which was heavily carved out so astronomers could easily see the plate under it. Pointers on the rete represented a number of fixed stars, which could be rotated over the tympan to show the passage of the stars relative to the astronomer’s latitude. On top of the rete was a clock-type hand called the rule, which could also be rotated in order to make calculations.

The reverse sides of most maters were engraved with a wide variety of scales. While the number and organization of these depended on where and when the astrolabe was made, all astrolabes included scales for measuring angles and scales for determining the Sun’s longitude for any date, as well as an alidade for measuring the altitude of celestial objects. All the interlocking parts were “fixed” by a bolt through the middle of each disc, rule, and alidade (so that they could rotate on top of each other), and fastened with a washer and decorative nut called a horse. The entire instrument was suspended by a string connected to a ring located at the top of the astrolabe. The Fusoris astrolabe’s rete and mater are constructed of gilt brass, but its single tympan, bolt, washer, horse, and suspension ring are of silver; the bolt head is further engraved with an 8 pointed star and the washer with a 16-point wind rose.

Although astrolabes were invented centuries earlier in the Arabic-speaking lands under Islamic rule, this particular astrolabe was made in the Parisian workshop of Jean Fusoris in 1400. Other astrolabes from this workshop contain four or five brass tympans with projections for four to eight European latitudes within the range of 40° to 56°. The Harvard example, however, has a single, silver tympan inscribed for 34°—the latitude of Fez and Rabat (Morocco), Sultanabad (Iran), Herat (Afghanistan), and within half a degree of Damascus and Baghdad. So, we can surmise that this astrolabe was likely expressly constructed for a client who needed a low-latitude instrument for use in the Arabic-speaking world.