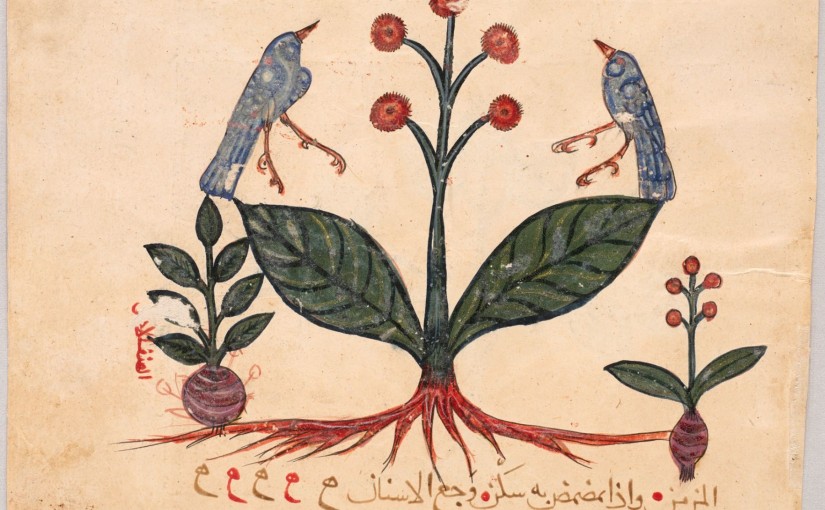

This is a folio (page) from an Arabic copy of an important ancient medical text by Dioscorides. It features the verbascum plant, and can be viewed online at the Harvard Art Museum’s site, or as part of the Google Art Project.

Dioscorides (Pedanius Dioscorides) was born in the first century C.E. in Anazarba, near Adana in modern-day Turkey. He had the opportunity to study the plants of many different regions (including Anatolia, Egypt, Arabia, Persia, Gallia, North Africa and Caucasia) while traveling with the Roman army as a military physician during the reigns of Emperors Caligula (37-41), Claudius (41-54) and Nero (54-68). He recorded this vast medical knowledge in Greek, but his monumental work Περί ύλης ιάτρικης (Peri hyles iatrikes) is more widely known by its Latin name, de Materia Medica (“On Medical Materials”). De Materia Medica describes more than 600 herbal drugs, about 35 drugs from animal sources, and about 90 drugs prepared with minerals, most of which are illustrated. The narrative descriptions provide specific information about those drugs, such as their places and methods of cultivation, botanical descriptions, medical effects, methods of use, side effects, dosages, veterinary usage and non-medical usage.

De Materia Medica was translated from Greek into Arabic and Syriac several times during the eighth century C.E. The first and most important of these translations was produced by a Greek and Arab scholar, Stephanos ibn Basilos and Hunayn ibn Ishaq, who worked together in Baghdad during the reign of the caliph al-Mutawakkil. Because Dioscorides included local names of plants from across many regions, however, Arabic translators struggled to find proper equivalent names for the plants. Some translators did not translate all the drug names, but instead transliterated many into the Arabic alphabet. Moreover, since the botanical nomenclature in the Arabic language was not as extensive as that found in de Materia Medica, the Arabic translators had to develop new terminology. Improved versions of this monumental work were made available in the subsequent centuries, especially in the Western Caliphate, and its information was incorporated in other major pharmaceutical works– for example, the writings of Ibn Sina, al-Razi, and ibn Juljul.

The copy of de Materia Medica from which this folio was taken likely would have served as a handbook for doctors, students or others seeking to harvest or use medicinal plants as part of their trade. As the text was copied and disseminated widely throughout Arabic-speaking world, refinements and small changes were made not only in the text but in the illustrations. By comparing extant manuscripts, scholars are able to reconstruct aspects of the transmission process.

Our folio also may have served an ornamental purpose. Wealthy elites in thirteenth-century Baghdad often commissioned illustrated manuscripts like this one, and an affluent patron could have paid a significant fee to have a personal copy of de Materia Medica as a status symbol. It is possible that a larger codex was split into individual folios and sold one by one. The light color of the paper (in the thirteenth century, light paper was relatively more expensive than darker grades), the scribe’s use of gold, and the fact that the folio has lasted centuries with little damage all point to its treatment as an object of admiration as much as (or more than) a tool of scientific inquiry.