House of God

The transformation of a place into a venerated site was precisely the effect of the events that took place there. Although the idea of a universal Christianity was to surpass all materiality, and any parochial, national, or spatial differences, the sacrosanctity of this particular place has called for its proper demarcation, veneration and protection: ultimately, by a built form, a church.

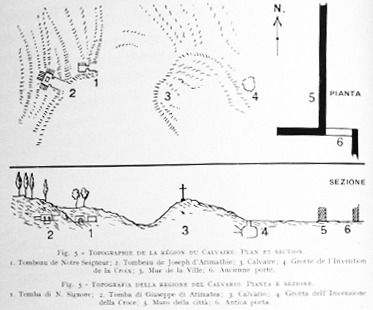

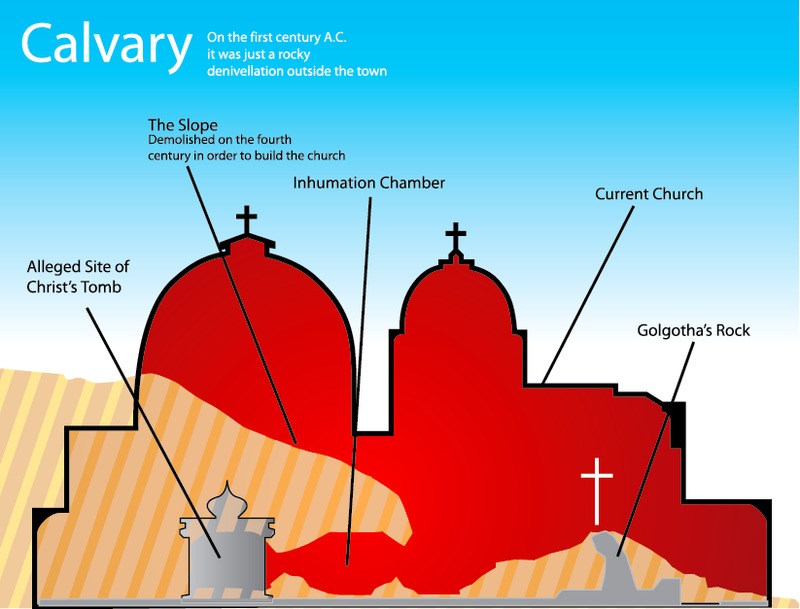

While a map of the global distribution of Christians might indicate the varieties of the religion’s multiple strands and denominations, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, as a built material space, tests these relationships in a close spatial setting. The first church at the site was built in the 4th Century, during Constantine the Great, to replace a Roman temple erected to hide the burial cave. The region’s tumultuous history has reflected on the church itself, as it has been destructed, modified, and reconstructed on many occasions up until the late 19th Century.

The birth of the church was both ideational - as depicted in El Greco’s Pentacost - as it was concrete. Both these aspects emanate from, and ultimately converge at the site of the Holy Sepulchre.

The idea of a universal religion was compromised once it encountered the reality; the diversity of geographical and cultural contexts that it spread to made Christianity take different denominational forms, often opposed, that all share an ambition of exclusivity and universality. However, once these different religious strands re-encountered each other on the site of their common source, the differences that could go unobserved on an ideational and global scale (and that are mitigated by discourses of ecumenism and interreligious dialog) became concrete and experiential. Thus, the ownership and control of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre have always been a troublesome issue, resolved only through a status quo that gives each Christian denomination the control of a precise area of the church, while the control of the access to the building is controlled by two Muslim families - one that holds the keys, and the other that has the right to use them.

The Holy Sepulchre is not only a concrete space of intense relations and high tensions, where different strands of once a single utopia reflect to the aura of their shared source; it is also a built map of that space that straddles the ideational and the concrete.