A Guide to Berlin

After the Bolshevik Revolution of 1929 and the Civil War, more than three million people fled Russia. For many, Berlin was the first place of refuge, and the biographies of nearly all of the most prominent intellectuals, artists, writers of the first-wave emigration include a Berlin chapter. In the early 1920s, the German capital became home to almost 400,000 Russian emigres. A vibrant center of the dispora, it was the first and most active center of emigre publishing between 1920 and 1923.

It was here that Valdimir Nabokov made his literary debut under the pseudonym V. Sirin, with his short stories and poems appearing in emigre periodicals, with his first novels published by Berlin-based publishing houses. The Berlin chapter of his creative biography is very rich, even though Nabokov never felt at home in the city. After fleeing Russia in May 1919, the Nabokovs settled in the German capital, and the young author visited his parents often while studying at Cambridge, moving to the city after graduation in 1922—the year his father was killed in Berlin, during an assassination attempt on the life of Pavel Miliukov, who was a prominent politician and proponent of constitutional monarchy in Russia. Having fled Nazi Germany in 1937 with his wife Vera and their son Dmitry, the writer never visited Berlin again.

Vladimir Nabokov's short story "A Guide to Berlin" (1925) features vignettes of the city seen from an outsider's perspective. The text does not simply capture the author's subjective impressions of Berlin, but rather can be seen as staging a dialogue with it—across space and time.

In this story, the city is written by an anoymous narrator, a "walker," in Michel de Certeau's terminology, one of the "ordinary practitioners of the city [who] live "down below'" and who explore it first-hand, moving through the crowds, weaving their bodies through urban fabric*. Our narrator shows no interest in the traditional historical and cultural landmarks of Berlin and presents a personal view of the city as seen from the perspective of a pedestrian.

The narrative makes it difficult, if not impossible, for the reader to follow in the narrator’s footsteps around Berlin, or to actually use his guide. The topography of Berlin in the story lacks geographical precision and is not clearly defined. The name of the city appears exclusively in the title, and the text includes only three, possibly four, landmarks that could actually be mapped: the Zoo, the Aquarium, the hotel “Eden” across the street, and the pub “Löwenbräu” where the two friends meet.

When the elusive Russian émigré who takes the reader on a tour of Berlin does give some indication of where a particular site is located, he is intentionally vague, as when stating that the roadworks he is watching from the streetcar take place “at an intersection,” or using a point of reference that the reader cannot know, as when situating the pipes “in front of the house where [he] live[s].”

The absence of identifiable landmarks, street names, exact locations is all the more striking in a story with a title that sets up the expectation that the text is written in the very genre that would require such information to be provided.

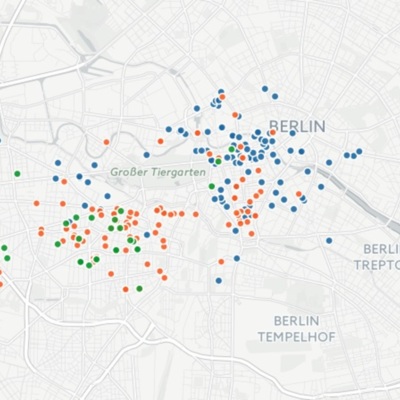

The three interactive maps illustrate the unconventional nature of Nabokov's "Guide."

Map 1 shows the historical sites of Berlin as presented in a 1908 official tourguide, as well as the major sites of Russian Berlin. Nabokov's story belongs to neither of these cultural spaces within Berlin exclusively.

Maps 2 and 3 show the position of the "landmarks" from "A Guide to Berlin" in relation to the sites of Russian Berlin and to the traditional landmarks highlighted in the tour guide to the city respectively.

note: The starting point of the narrator's journey through the city is his home in Berlin. It is worth noting that the narrator of the story should not be identified with the author himself, but for the sake of plotting that point on a map, the location of the house where Vladimir Nabokov was living at the time of writing "A Guide to Berlin" was used.

[*Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, trans. Steven Randall (Berkeley: University of CA Press, 1984) 93.]