Reading Aloud, Allowed: Two Readings of Anne Sexton's "Music Swims Back to Me"

If you’ve ever sent off a text message and suddenly realized that it didn’t come out quite the way you intended it to, you have probably already had this debate with yourself. Is it in what you say, or more so how you say it?

In many ways, this is often the essential question in poetry – is the written poem the final product, or the script for something more? Are we even meant to read poetry aloud, or by doing so have we entirely changed it's meaning? Countless authors have asked the same question in many ways, including Jonathan Culler, whose “Very Short Introduction to Literature” dedicates an entire chapter to the rhetoric of poetry and the ways in which we truly derive meaning from poems. Here we’ll use two readings of Anne Sexton’s famous poem “Music Swims Back to Me” to analyze the differences between the written and spoken versions.

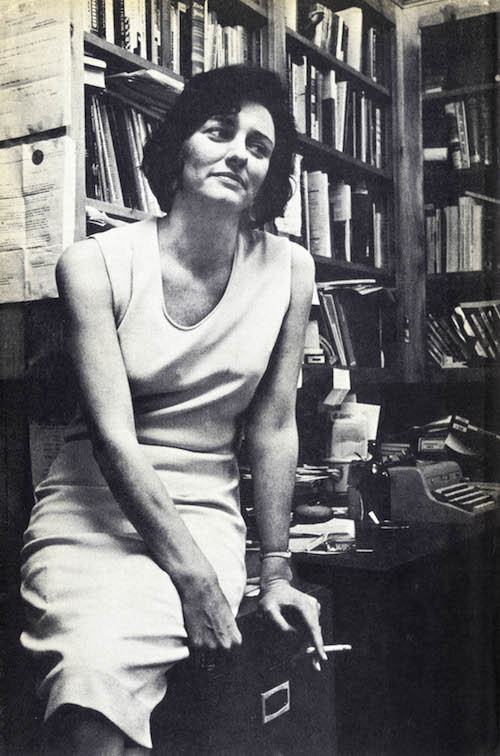

Anne Sexton was a renowned poet who was encouraged to take up poetry after her many struggles with mental illness, quickly coming into her own as an acclaimed writer. She studied at Boston University with other revered poets like Sylvia Plath, mentor W.D. Snodgrass, and Maxine Kumin, who became Sexton’s dear friend (Middlebrook, Morris, Carrol). Kumin went on to describe Sexton’s intense and unabashed poetry style, saying "She wrote openly about menstruation, abortion, masturbation, incest, adultery, and drug addiction at a time when the proprieties embraced none of these as proper topics for poetry." (Colburn). Though Anne Sexton was known for several of her works, especially her final two collections, “Music Swims Back to Me” is known in particular for its creative diction and artful imagery. Here, we will compare two of Anne Sexton’s own readings of this poem. In the interests of unbiased reading and listening – or at least as unbiased as possible – I have chosen not to include the author’s introductory remarks for each reading and instead to focus exclusively on the text of the poem. In order to really compare the two and find differences in the meaning conveyed by having the poem read aloud, we must not allow the author’s own changing perspective or commentary to influence our preconception before each reading. The full text of the poem and links to each of the readings are available, below:

MUSIC SWIMS BACK TO ME

Wait Mister. Which way is home?

They turned the light out

and the dark is moving in the corner.

There are no sign posts in this room,

four ladies, over eighty,

in diapers every one of them.

La la la, Oh music swims back to me

and I can feel the tune they played

the night they left me

in this private institution on a hill.

Imagine it. A radio playing

and everyone here was crazy.

I liked it and danced in a circle.

Music pours over the sense

and in a funny way

music sees more than I.

I mean it remembers better;

remembers the first night here.

It was the strangled cold of November;

even the stars were strapped in the sky

and that moon too bright

forking through the bars to stick me

with a singing in the head.

I have forgotten all the rest.

They lock me in this chair at eight a.m.

and there are no signs to tell the way,

just the radio beating to itself

and the song that remembers

more than I. Oh, la la la,

this music swims back to me.

The night I came I danced a circle

and was not afraid.

Mister?

In her earlier reading of “Music Swims Back to Me,” in 1959, Anne Sexton’s voice is bright and lilting, and through the entirety of the poem she speaks melodically, emphasizing key consonants and stressing certain words. She pauses for a long while after “Wait Mister!” before continuing on, and her voice rings with innocence when she asks, “Which way is home?” She lingers on the consonants in the words “moving” and “corner.” As she describes the lack of signposts and the women in the room, she takes on a steadier rhythm and a stronger tone unless she arrives at the first “la la la,” which is, interestingly, one of the least musical and melodic lines in the entire reading. As she reflects on the memory of the music, her tone is deeper and her speech slows somewhat, as though seeming to drag a bit backwards. She takes more frequent breaths, implying a kind of exhaustion or inability to go on. When she cries “Imagine it! A radio playing and everyone here was crazy...” her voice takes on a new whimsy and excitement, almost like that of a newscaster or an advertisement, which contrasts starkly with the negative, dark images portrayed by the text itself. In the following section, Secton’s voice grows softer and more distance, paralleling the reflectiveness and somber tone of the text as she describes the music’s ability to remember. On the lines, “It was the strangled cold of November; even the stars were strapped in the sky, and that moon too bright, forking through the bars to stick me, with a singing in the head,” she once again emphasizes consonants and pauses between almost every key word, her voice sharp with a crisp sort of anger or defiance. The final stanza rings out at a higher pitch, warm with the same innocence of her initial “Which way is home?”

In the 1974 reading, however, Anne Sexton’s voice is much smoother and lower throughout, and the bulk of her emphasis is on the vowels and hummed sounds in the words rather than the crispness of the consonants. Many of the pauses from the previous reading are absent, and the whole poem seems to be read in a series of swells from lowest to low and back down again rather than up to any major high points. There is also an element of monotony or numbness to the second reading, almost as if the poem’s narrator has lost herself almost entirely and speaks on autopilot rather than reflecting actively on her experiences and memories. There are brief pauses after her initial “Which way is home?” and the description of the elderly ladies, but very little rhythmic speech is present in the first section, and the first rendition of “la la la” is deep, throaty, and exhausted, almost as if the music is playing the same note incessantly in her mind. In the next section, Sexton’s voice swells only briefly and then settles in both speed and pitch, as if the words are too heavy to speak crisply or highly. Again she peaks with a bit of enthusiasm at “Imagine it!” but it is nothing like the cheerful announcing tone in her first reading. The line “everyone here was crazy” rings out loudly and brightly on the word crazy, but immediately afterwards settles into a low-pitched melancholy on “danced in a circle,” drawing attention to the tonal shift in the text itself from first a memory to a realization of what had happened to her. Throughout the remainder of the poem, Sexton’s voice and emphasis seem almost to droop until she reaches the final weak, soft “Mister?” at the end, leaving listeners with a far sadder feeling than her previous reading which seems instead to be more narrative.

The differences between these two readings, of course, lie entirely in Anne Sexton’s voice and inflection – between them the words are exactly identical, and yet listeners leave each reading with a somewhat different sense and modified understanding of the words themselves. Nonetheless, at its core the poem’s story is clear in both readings, so it becomes impossible to say that the meaning lies entirely in either the text or the reading thereof. Rather, it seems that the text is the outline, the black and white page left uncolored by personal experience, by inflection, by sound. It is reading aloud, performing, expressing that text in someway that colors in the lines and modifies the text from its most neutral form. So, really, it’s not just what we say or just how we say it... it’s what we say, how, and of course, to whom.

REFERENCES:

(Recordings of Anne Sexton's performances of "Music Swims Back to Me" can be found at: http://hcl.harvard.edu/poetryroom/listeningbooth/poets/sexton.cfm.)

Culler, Jonathan D. Literary Theory: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1997. Print.

Sexton, Anne. "Music Swims Back to Me." To Bedlam and Part Way Back. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1960. N. pag. Harvard Library. Web. 07 Mar. 2016.

Carroll, James (Fall 1992). "Review: ‘Anne Sexton: A Biography’". Ploughshares 18 (58). Archived from the original on November 4, 2007. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

Morris, Tim (1999-04-23). "A Brief Biography of the Life of Anne Sexton". University of Texas at Arlington. Retrieved 2009-02-20.

Middlebrook, Diane Wood. Anne Sexton: a biography. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (HMH), 1991.

Anne Sexton (1988) Steven E. Colburn, University of Michigan Press, 1988 p438 ISBN 9780472063796